More common and more normal than you think!

Introduction and Premise

A difference of sex developmentis described as a congenital and significant difference to the chromosomes, gonads, internal reproductive organs, genitalia and sex hormone profile. For clarification on what a difference of sex development (DSD) is, please see the Intro to Intersex page.

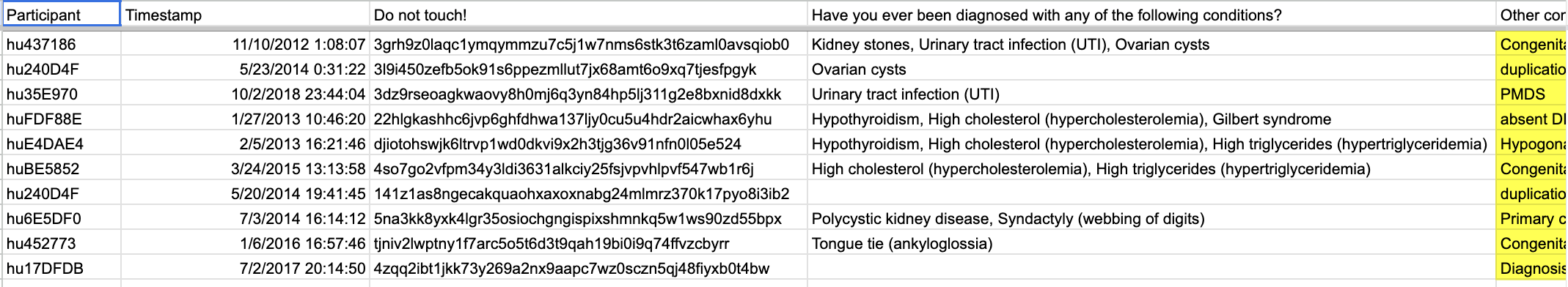

One of the numbers commonly cited regarding the occurrence of DSDs/intersex conditions is 1.7%, but this is an estimate and it is frequently debated. Some researchers argue that it’s much rarer, occurring at a rate of 1 out of 10K, and have defined DSD as only those with ambiguous genitalia. These are some huge differences in estimation, and it does not help that over 70% of those with a DSD do not receive a specific or accurate diagnosis. Therefore, we will take to a random population sample who have submitted their human genome data to Havard Medical School to look for incidence of likely DSDs, even if they were not reported as a DSD.

Data Analysis

Please see the following data sets (Metabolic/endocrine, Genitourinary, Congenital Anomalies) for the raw data and tables made for analysis. Additionally, the interview sources and additional relevant studies are cited in the sources page.

Some questions answered by this data analysis will be:

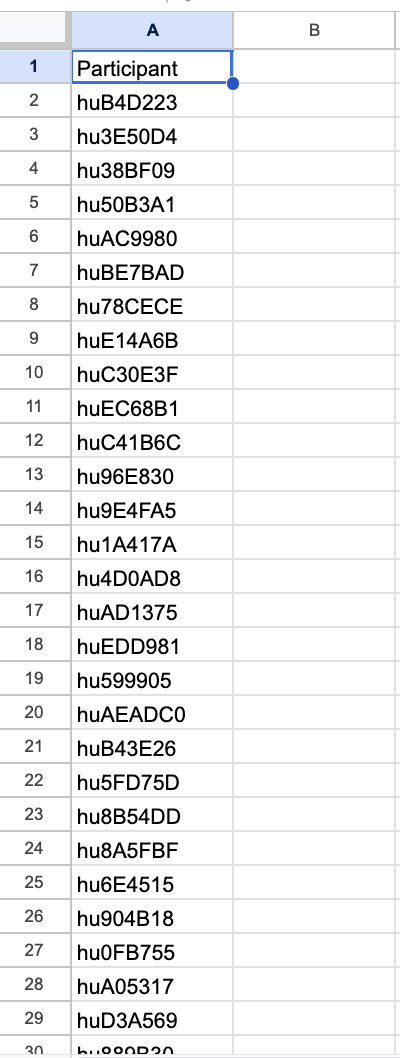

What is the total amount of unique respondents across the three data sets?

- Import CSV file into Google Sheets

- Copy Column A of all sheets into a new spreadsheet into Column A of the new sheet

- Create pivot table

- Values: Count unique

Return: 2318 unique participants

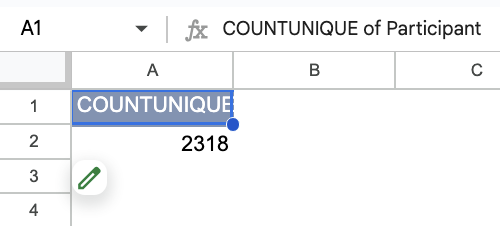

How many people had a condition not otherwise listed compared to the number of people who had any diagnosis in each data set?

- Sort Data Range (advanced)

- First sort by Column D

- Then sort by Column E

- This should return total number of respondents with diagnoses

- Copy sorted data into a second sheet — include only the diagnoses

- However there are respondents who write “no”, this can be addressed

- Delete all the cells that say no/none/n/a after Column D starts giving blanks and then delete the rows

- Do this for the other two data sets

Endocrine/metabolic/nutritional/disease survey Total: 1243

Congenital Traits and Anomalies Survey Total: 314

Genitourinary disease/anomalies Survey Total: 1133

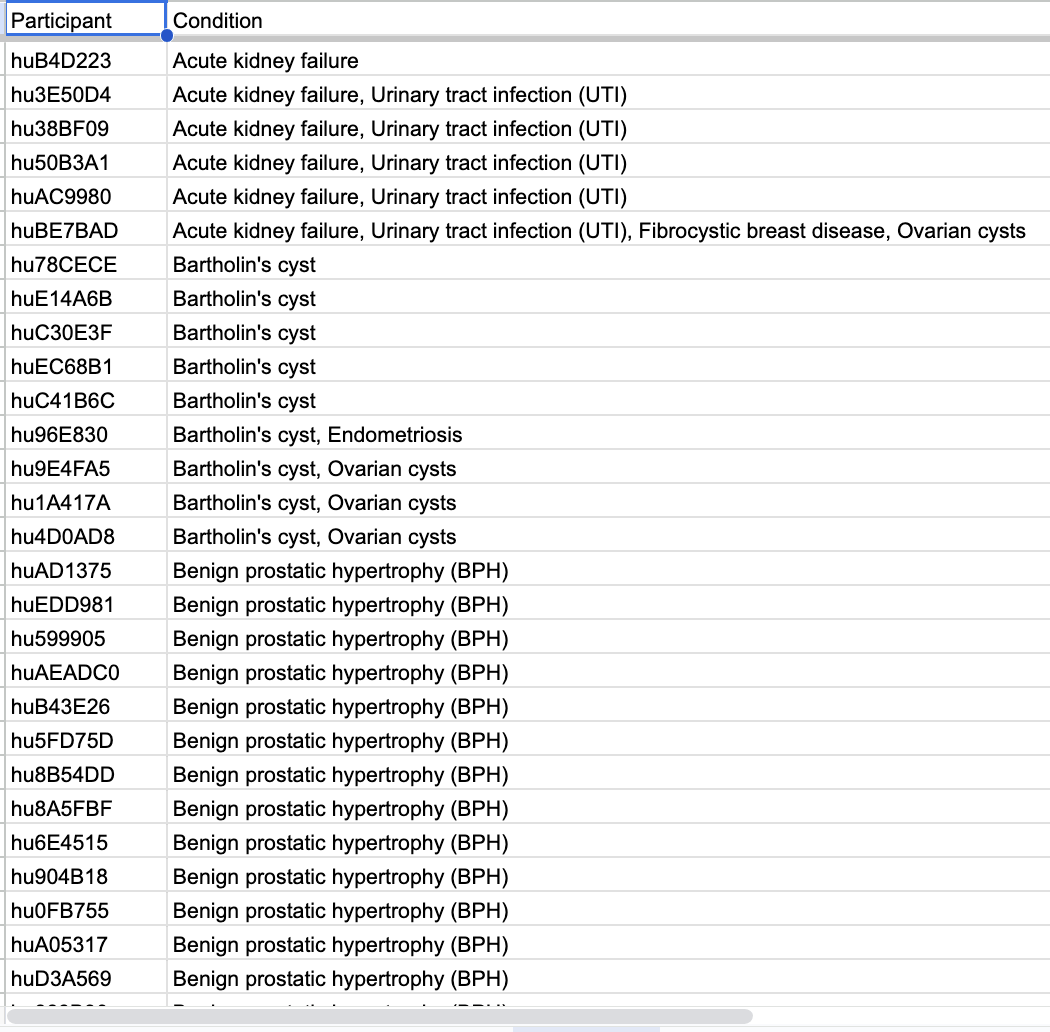

- In the copied sheet, insert row and create a header row

- Label column A diagnosis and column B not listed

- Select all, create a filter

- Filter out blanks

- Copy filtered column B and paste into third sheet, which will give the value of all conditions not listed

- Do this for all sheets

Other conditions Not Listed:

Endocrine/metabolic/nutritional/disease survey: 179

Congenital Traits and Anomalies Survey: 143

Genitourinary disease/anomalies Survey: 157

How many people in the survey have a likely DSD?

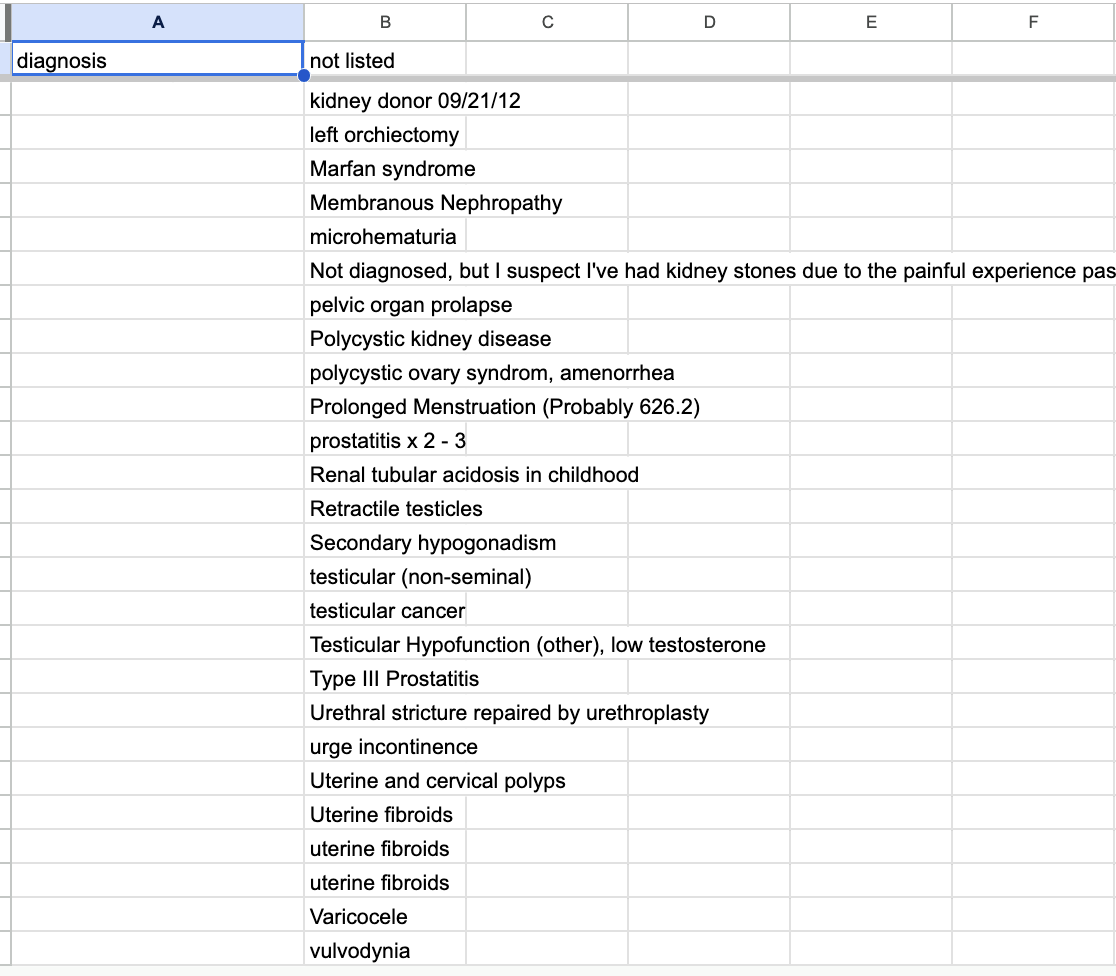

It doesn’t seem like there is an option listed for DSDs in the second column where participants select from a list of conditions. This means it is likely to be in Other Conditions Not Listed.

- Create filter view

- Sort “Other Conditions Not Listed” (Column C) by Condition

- Deselect Blanks

- Do this for each sheet

- From this point onwards, specialty knowledge regarding DSDs is required. I have co authored studies on DSDs and facilitate research and support groups for people with DSDs. Therefore, I have extensive knowledge about differences of sex development. I have shared my understanding of DSDs on another page in this repository, and you may read more about it here.

- Isolate conditions that fit the criteria of DSD (congenital significant difference to the sex characteristics)

- Highlight each relevant condition across all three sheets

- Exit filter view for each sheet

- Create new filter view

- Filter column C by colour

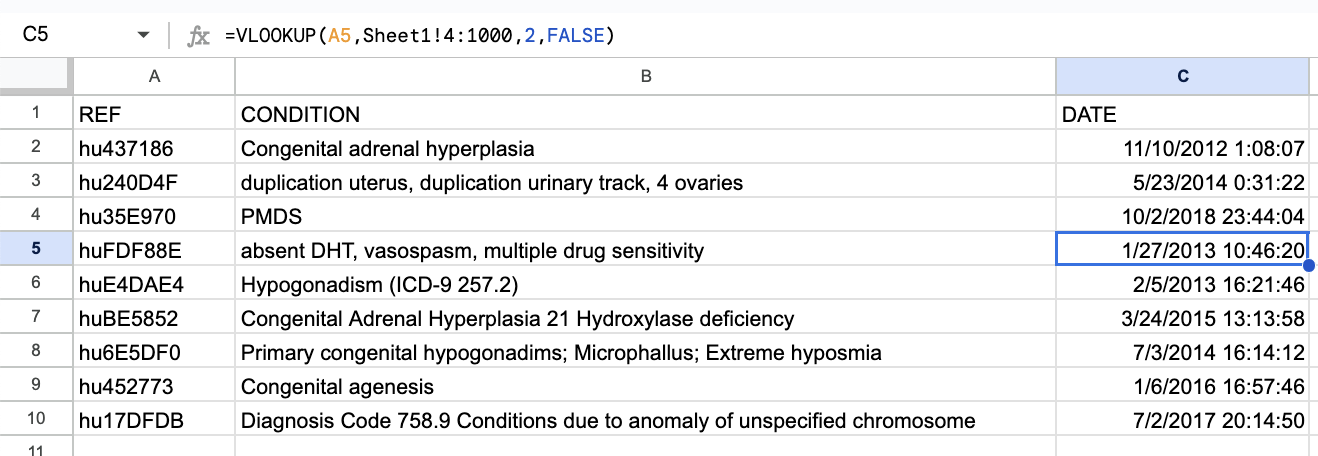

Now, let’s double check that there aren’t any duplications

- Copy the highlighted results over to a new sheet from each data set (Sheet1)

- Create Sheet2

- Copy Column A (patient reference numbers) to Sheet2

- In cell B1, write a VLOOKUP formula

- =VLOOKUP(A1,Sheet1!$A$2:$E$15,5,FALSE)

- Drag the cell all the way down to the end of the values in Column A

- Create new filter view

- Filter out blanks

- Go to Data

- Cleanup -> remove duplicates

- Select column A

- One of the references was duplicated, so the extra was removed

There are a total of 9 references who have a condition that fits clinical definition of DSD

What is the incidence of reproductive disorders/anomalies compared to general endocrine disorders?

- Go to sheet with just the diagnosis and not listed categories

- Make a pivot table

- Filter by diagnosis first

- Select all reproductive disorders, deselect non reproductive disorders

- Obtain CountA value

- Make second pivot table

- Filter by not listed

- Select all reproductive disorders

- Obtain CountA value

- Filter by diagnosis now

- Obtain CountA of the overlap

- Add the first and second CountA, then subtract the third

115+32-5 = 143

Incidence of reproductive disorders in the Endocrine sample is 143

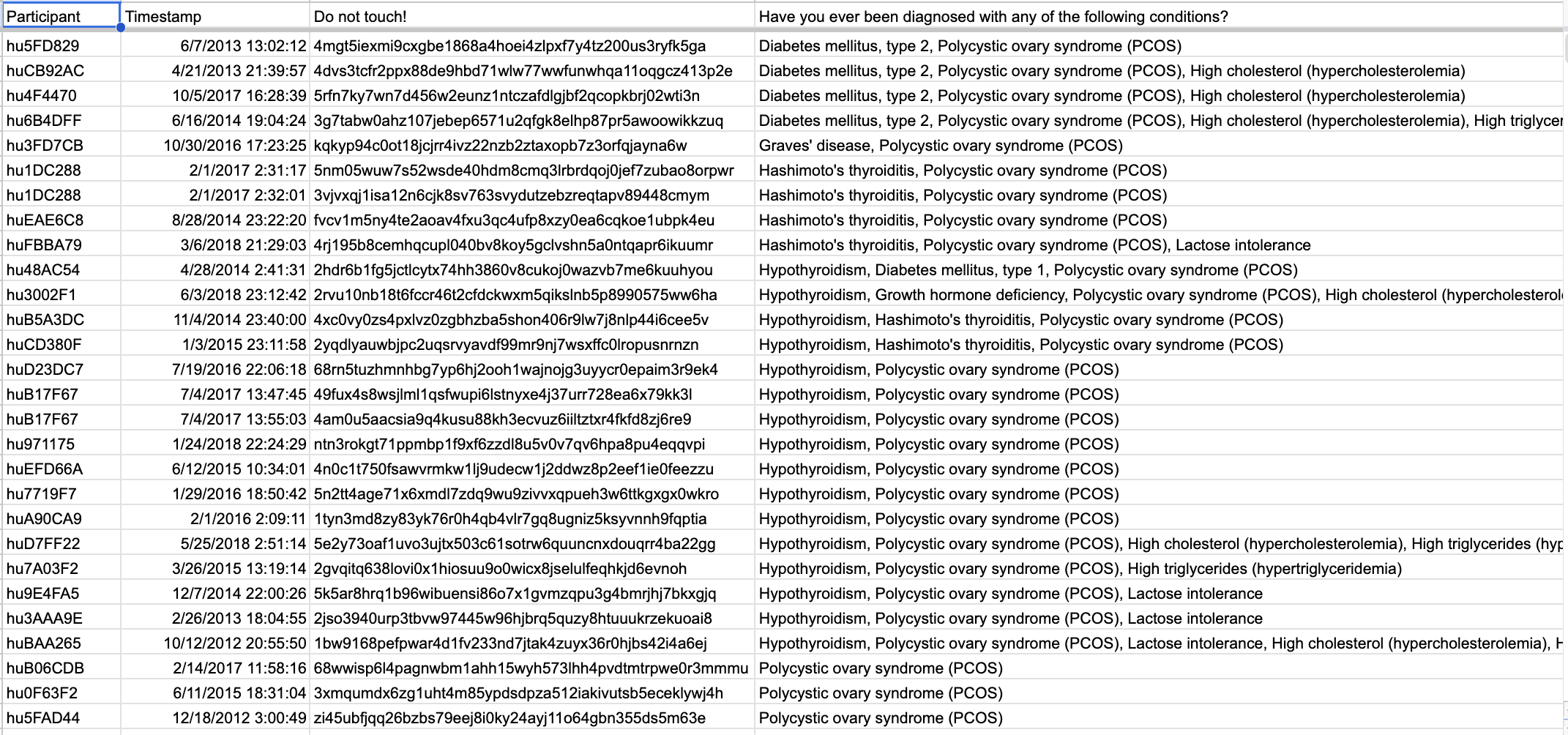

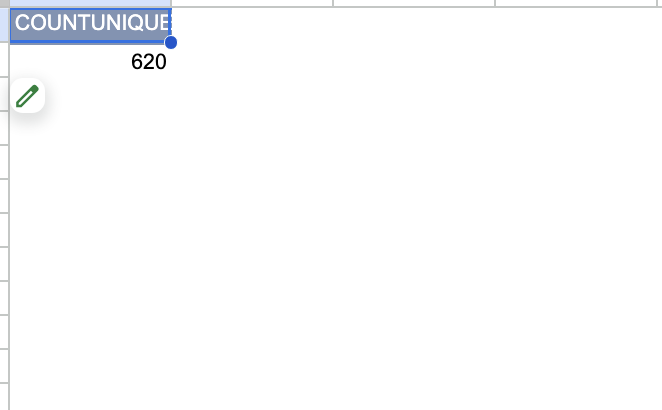

What is the incidence of reproductive disorders in the entire sample size?

- Create a filter for the entire sheet and a new filter view

- Filter by diagnosis for reproductive disorders

- Copy and paste results onto a new sheet: SheetRepro

- Exit filter view, and then filter again by conditions not listed for reproductive disorders

- Copy and paste results onto SheetRepro under the previous paste

- Remove the header row if it was pasted

- Repeat process for the other two data sets, pasting under the previous filtered data in SheetRepro

- Once all the data is in SheetRepro, insert a pivot table

- Add value for Participant

- CountUnique

Incidence of reproductive disorders in the entire sample size is 620

That was a lot of data and numbers! Let's contextualize it a little bit with some visualizations

It’s just that we are overall, not knowledgeable about reproductive biology or science in general

Let’s take a look at how much the average person knows about reproductive biology (sourced from a study on general scientific literacy).

The Problems Facing Medical Care and Diagnosis of DSDs

What this data shows us is that first of all, DSDs are more common than people tend to think. Additionally, we can observe that there are various issues with the survey design itself that may make it difficult for people to disclose their conditions — there was no option to disclose a DSD in the prewritten diagnosis options. Even one of the most common DSDs, Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia, had to be voluntarily written and disclosed. This means that survey respondents may end up not disclosing their diagnosis because of the extra effort it requires. Through survey design alone, we can assume that this number may be lower than the actual rate.

In addition, rates of misdiagnosis or lack of proper diagnosis for individuals with DSD is high. Only around 13% ever receive genetic sequencing to narrow down the likely cause, and there is a 40% chance of misdiagnosis for patients. Additionally, for those who have gone undiagnosed or lacked a concrete diagnosis, 97% had never done any genetic sequencing. This is a deeply concerning metric, because it implies that the majority of people with DSDs may be going misdiagnosed or undiagnosed altogether. If we observe the table above, more than half of the individuals could not actually provide a diagnostic name for their condition. We also know that certain DSDs like Turner’s syndrome or Klinefelter’s syndrome occur at 1 out of 2000 and 1 out of 1000 respectively, and one would have expected to see their appearance. However, these DSDs were not seen, and it can be hypothesized that several instances of unexplained male or female infertility could be caused by one of these DSDs, that was never tested or diagnosed.

Note that in the dataset, more than half of the respondents experienced some type of endocrine issue, and over a quarter had experienced a reproductive disorder of some kind. The issues that face those with DSDs are not unimaginable for those without DSDs – to make a simple comparison, Congential Adrenal Hyperplasia resembles PCOS in many ways, including hirsutism and acquiring ovarian cysts, except CAH will often present with some level of genital ambiguity. When more common conditions like PCOS or male secondary hypogonadism are treated with professionalism, DSD care continues to lag behind in terms of medical and ethical competency. The “rarity” and “too different” argument does not hold in the face of both the similarity of DSDs to various “common and milder” reproductive or endocrine conditions, and how common it is to have any kind of reproductive problem. DSDs are also not rare enough to justify the lack of medical incompetency and ignorance about the topic that those with DSDs frequently experience. There is an incredible amount of stigma and shame surrounding DSDs, which is often unwarranted and constructed by clinical narratives that frame those with DSDs as alien, defective, and too difficult to treat.

I interviewed one of my colleagues who helps with an intersex community initiative to get her opinion on the findings. Her name is Klara, and she has XX/XY Chimerism, and has spent many years assisting those with DSDs in understanding their medical documents, pursuing adequate medical care, as well as advocating for the end of intersex infant cosmetic genital modification.

Interview

Here is what Klara has to say:

Me: Before I show you what the data says, what do you think the occurrence rate is?

Klara: It’s most likely closer to the higher estimates, but not the highest estimate. There is a lot of stigma about disorders of sex development, whether acquired or congenital. In this specific case, because society itself values belonging to a binary sex category, the stigmatization of intersex conditions will make people wary of being diagnosed of being intersex themselves or having their children be diagnosed with a DSD/intersex condition. This may make them feel like they no longer belong to a clear sex category, and this can make them feel damaged in some way. Alternatively, people may also seek medical justification for concerning symptoms, but reject the label of a DSD.

Me: The occurrence rate is about 1 out of 200 in this sample, what do you make of that?

Klara: Considering there is so much shame about DSDs, this only means that 1 out of 200 people have some medical evidence or partial diagnosis of being intersex. There are a lot of people whose diagnoses are hidden from them, or described as something else — given the shame around infertility. It is hard to say about whether this statistic is actually representative of the actual amount of intersex/people with DSDs in the population.

Also, some people may not want to be diagnosed because there are laws and policies that favour transgender people and discriminate against intersex people. Intersex people may face extra scrutiny if they wish to correct a faulty initial birth assignment, even if the corrected assignment is closer to their actual anatomy. Due to these legal trappings, some intersex people prefer to let the legal system think that they are trans up until they get the gender marker changed, and may pursue diagnosis later. They may not feel comfortable disclosing even to an anonymous survey.

Me: The survey itself may also be ill designed for DSD respondents. The listed options do not include an option for DSDs — if you were taking this survey, would that influence whether or not you disclose?

Klara: Yes, because it will make me wonder if that condition is even relevant to include, and I may also just not feel like I have the energy to fill that in by hand in a presumably long survey. It makes me feel like an afterthought. I very much believe that given the lack of knowledge about reproductive biology, people do not and will not know anything about DSDs, and this absolutely hinders their access to diagnosis and medical care.

So what can we conclude from this analysis of a random population sample?

We can conclude that even with subpar medical care and lack of awareness, DSDs are more common than researchers and popular media like to claim. When misdiagnosis as well as malpractice is common enough to become an expected pattern in the treatment and care for those with DSDs, this indicates a serious issue. Intersex youth and adults are frequently given unnecessary gonadectomies (sterilization), genital modifying surgeries, and many are pushed into this without even an accurate diagnosis. It had previously been argued that the lack of competency was due to the rarity of DSDs, but this population analysis as well as many other sources are showing that DSDs are nowhere rare enough for this to be a good reason.