What is Intersex (Difference of Sex Development)?

Before you read this introduction to DSDs/Intersex, there is a refresher for those who feel they may be shaky on reproductive biology knowledge. Here is a quick review of how sex is defined and differentiated.

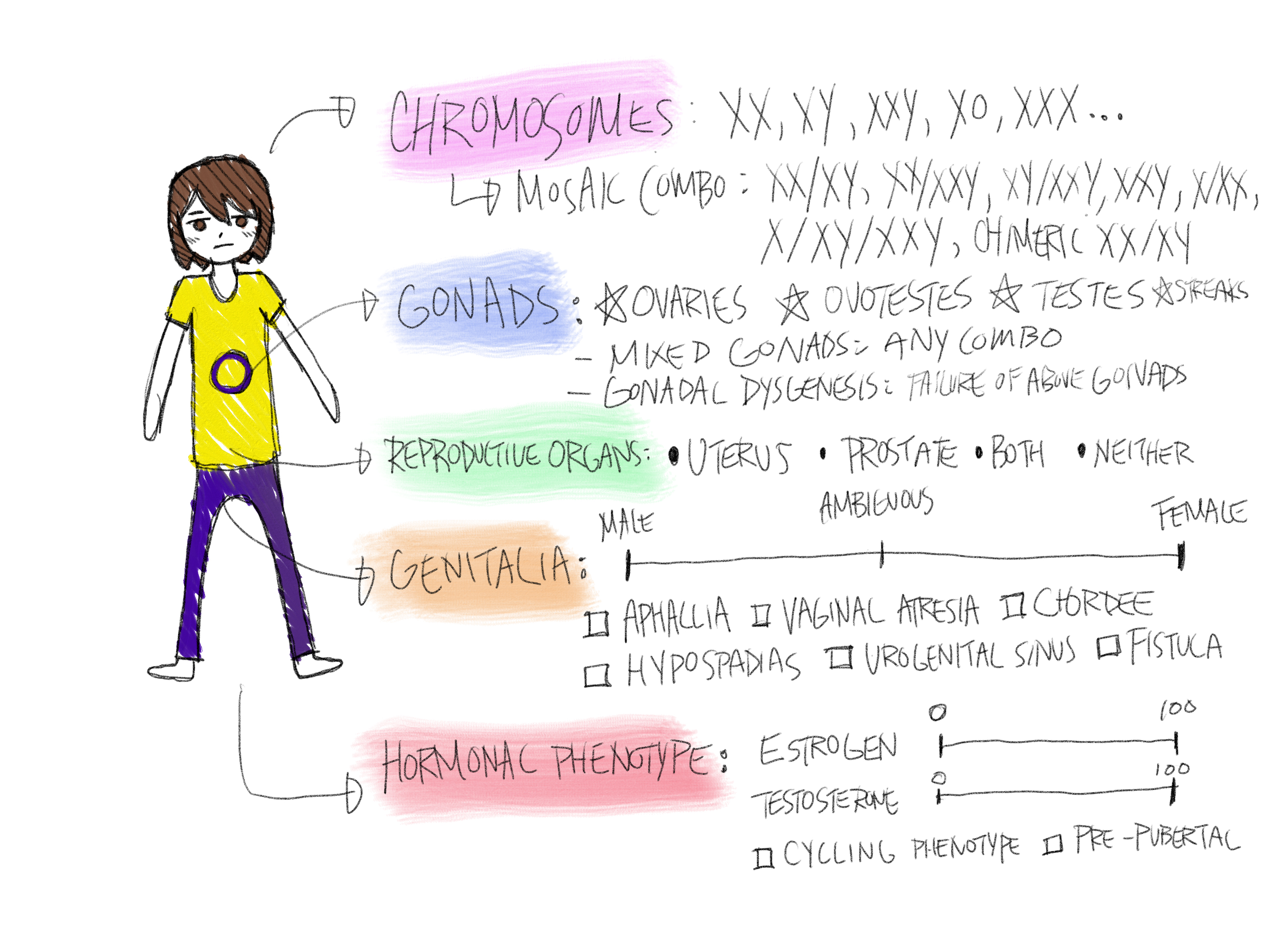

So now that we know how typical biological sex works, and how sex is determined in most cases, we can visit and define a difference of sex development, which is more colloquially known as an intersex condition. Difference of sex development (DSD) is the medical term for an individual who has a congenital and significant difference in their primary and secondary sex characteristics. This means that the individual has a significant difference in at least one of the five sex determinant characteristics that makes their set different from the typical: chromosomes, gonads, internal reproductive organs, genitalia and endocrine composition. This is a truly broad category, encompassing over 40 known conditions and with others that have yet to be classified or discovered. Around 0.5-1.7% of the population has an intersex condition/DSD, meaning that every large lecture hall at university will statistically contain at least one intersex person. For a relatively unknown phenomenon, it is quite common.

It is also understandable right now, that you may find this difficult to visualize or fully comprehend — most of us have never heard of DSD before, and it is hard to imagine something believed to be fundamental like anatomical sex being naturally different. And now, you are told there are over 40 different variations — most anyone would be grasping at straws. This is why I have created the categories below to better understand.

Differences of sex development can be largely sorted into three different categories of their root cause:

Chromosomal

Sex determinant gene mutation

Sex hormone synthesis/receptor differences

All of the currently known DSDs are located in another page, and if you are interested, you may look here for the comprehensive list.

1. Chromosomal DSDs

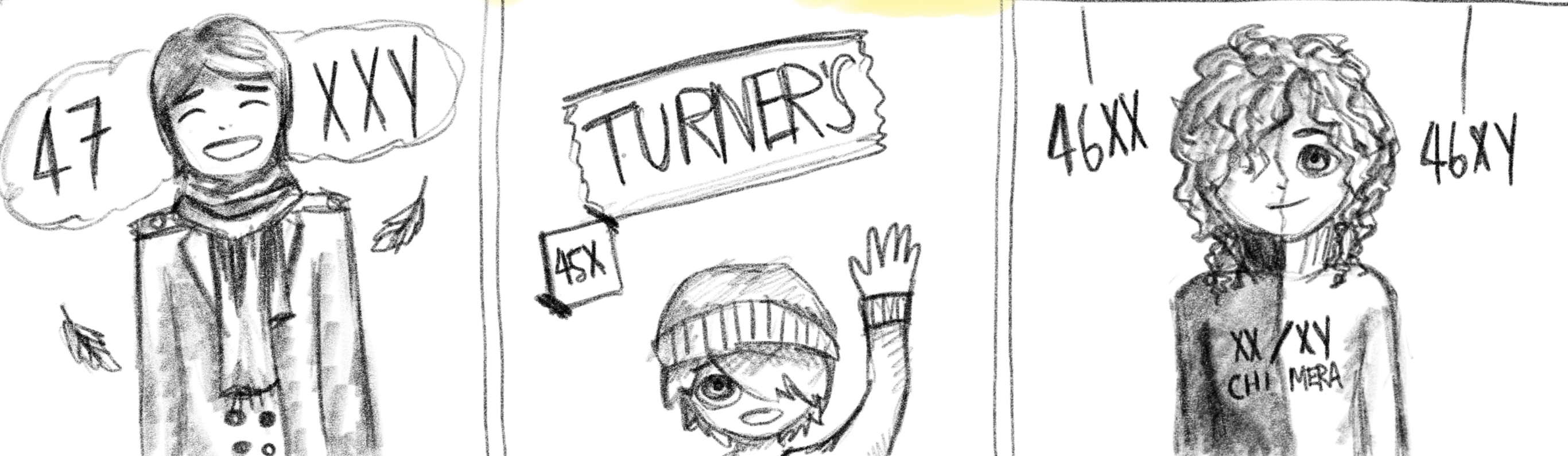

Chromosomal DSDs are defined by a difference in sex chromosome composition, meaning that the individual has a sex karyotype other than XX or XY. There can be a number of different compositions, with some more common than others. For example, having only one X chromosome, Turner’s syndrome, occur in 1 out of 2000 births. Similarly, having XXY chromosomes (often correlated with Klinefelter’s syndrome), occurs in 1 out of 1000 individuals. Other combinations can be mosaicism, which means that some cells have one karyotype and some cells have another. Another type is chimerism, which means that a pair of fraternal twins fused in the womb.

So how does this occur in the womb? A chromosomal DSD is determined often before an egg is even fertilized. Remember how we established previously that in typical sex determination, the sperm’s sex chromosome component determines whether the fertilized embryo will be XY or XX? A chromosomal anomaly can occur if the sperm lacks a sex chromosome component, result in the embryo simply being X, or the sperm carries extra chromosomes (XY sperm for example), resulting in the egg being XXY. In some cases, the egg carries an extra chromosome component, and an XX egg can result in an XXY embryo or an XXX embryo.

Chromosomal anomalies can also occur during cell meiosis and mitosis, when the fertilized egg begins to duplicate and grow into the embryo. An XY cell may split into X and XY, with one of the cells dropping an X. This would result in two different cell lines in the body, one being X and the other being XY, forming the case of XY/X mosaicism. Similarly, XXY may split into XY/XXY, or XX/XXY, and a number of other combinations. Sometimes the fertilized egg starts out with XXXY and due to the instability of this karyotype, splits into the more stable XX/XY, resulting in XX/XY mosaicism.

Finally, a unique cause of chromosomal anomaly is chimerism, where there are two embryos to begin with, but one embryo dies and its material is absorbed into the other. This will result in a fetus whose body contains two sets of DNA altogether (so not just two or more sex karyotypes).

How does this difference in sex chromosomes affect sex development? The answer to this is complicated. Sometimes, no effect happens whatsoever if the individual has mosaicism and the fragmented cell lines simply do not reach the gonads. Other times, mosaicism may cause one gonad to be a streak (a primitive group of cells that don’t grow into an organ), and the other to develop normally. It could cause ovaries to have a little bit of testicular tissue, and thus cause genitalia to develop resembling male. Similarly, it could cause testicles to have some ovarian tissue, and cause the development of a uterus in someone who otherwise developed male. It could also cause ovotesticular DSD, where one or both gonads is an ovotestis (a mix of ovarian and testicular tissue) or for the individual to have one ovary and one testis (and in the case of chimerism, two ovaries and two testes).

For non mosaic chromosomal anomalies, such as Klinefelter’s and Turner’s syndrome, the extra or missing chromosome can affect the function of the reproductive organs, resulting in ovarian dysgensis in the case of Turner’s syndrome because of lacking genetic stability and testicular dysgenesis (or more specifically, dysgenesis of the seminiferous tubules) in Klinefelter’s syndrome as a result of incomplete X inactivation.

2. Sex determinant gene mutation

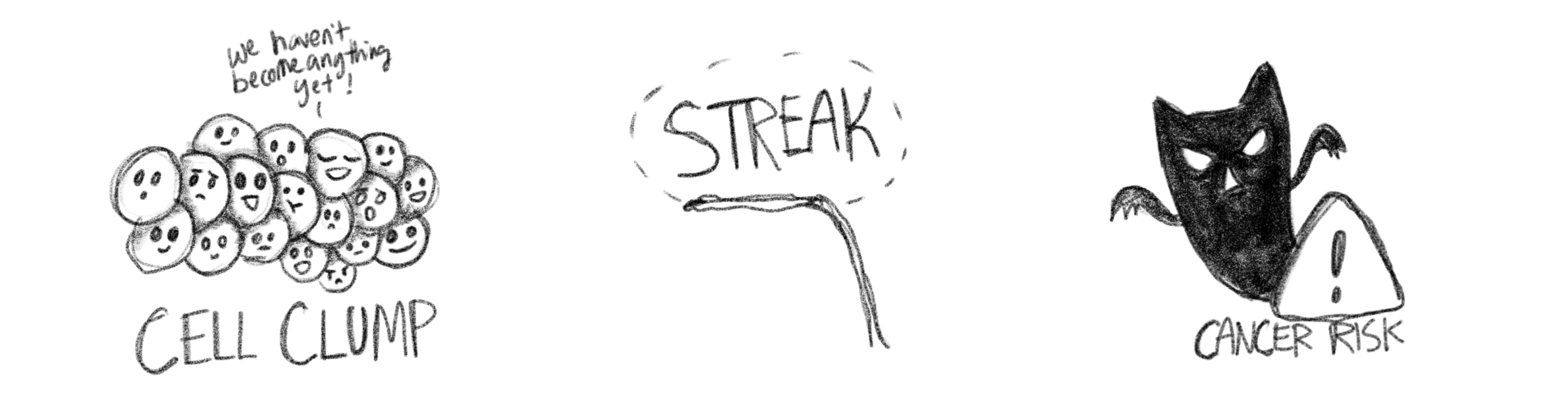

Sex determinant gene DSDs are defined by a mutation to one of the many genes that activate during fetal sex/gonadal differentiation, in someone with a typical XX or XY karyotype. As previously explained in the introduction to reproductive biology, sex is determined by the sperm, which will usually create an XY or XX karyotype. However, from this point onwards, a varied set of genes will govern how sex differentiation progresses. The SRY gene was mentioned as being crucial to the development of testes, and an XY fetus that lacks the SRY gene (XY sex reversal, Swyer’s) will develop female internal anatomy like the uterus, cervix and vagina, with female outer genitalia. Without the SRY gene, the testes wouldn’t form, and thus, the body default forms the female internal organs. However, because the fetus lacked the specific genes for ovarian differentiation due to the otherwise normal XY karyotype, an individual with Swyer’s possesses no ovaries, and will have streak gonads (non functional cell clumps) instead. Similarly, XX sex reversal, or de la Chappelle syndrome, works the exact same way with an XX karyotype that has acquired an SRY gene, which results in male genitalia, and working testes that produce testosterone but are unable to produce sperm.

Other sex determinant gene mutations include agonadism or aphallia, which results in no gonads or no penis/clitoris. MRKH is the name of a condition where a genetic mutation causes a typical XX female fetus to not develop a uterus (while still having ovaries and female genitalia). XX or XY OTDSD is caused by a mutation to several genes that regulate gonad differentiation, and will cause an individual to develop ovotestes or mixed gonads. There are a number of sex determinant gene mutation DSDs, and they will all be listed below.

Those with sex determinant gene mutations can appear in a variety of ways, but tend to not have any musculoskeletal or autoimmune issues that can be associated with those with chromosomal anomalies. Individuals with Swyer’s, agonadism, de la Chapelle, leydig cell hypoplasia, SF-1 mutation and similar mutations that cause gonads to have difficulty functioning, will require exogenous hormones to ensure pubertal development occurs/is completed and that bone density remains at a healthy level. While gonadectomy (removal of the gonads: ovaries, testes, or ovotestes) is never recommended and should not be done as an elective surgery for minors, the one exception where gonadectomy for the safety of the patient is in cases where one has streak gonads. Streak gonads have a high chance of developing cancers (most commonly, a gonadoblastoma), and they are unable to produce any hormones or gametes (sperm/eggs).

3. Sex hormone synthesis/receptor difference

Hormone synthesis/receptor differences are a category of DSDs that result from the congenital lack of certain hormones or excess of hormones, that causes differences to genitalia and/or pubertal development. We know now that sex is determined by chromosomes and sex determinant genes, which provides the genetic material and the activation of that material to differentiate between testes and ovaries. However, from this point onwards, the genitalia and internal reproductive organs is determined by the presence or absence of various hormones produced by the gonads. Testosterone produced by the testes will differentiate the internal male reproductive genitalia like the prostate and seminal vesicles, while dihydrotestosterone (DHT), which testosterone converts into via an enzyme, is crucial to developing the outer male genitalia (penis and scrotum). A lack of testosterone/lack of DHT influence will cause male genitalia to be absent, and the fetus will default primitive genital organs to female. The release of the hormone AMH (anti mullerian hormone) determines whether or not a fetus develops a uterus, and this hormone is primarily produced in the testes.

So how does a difference in hormone synthesis manifest? In the case of androgen insensitivity, a mutation to receptors, or the body’s ability to process testosterone, is either completely absent or partially absent. This means that even though an XY fetus will have testes, their body is immune to testosterone, and thus the genitalia develops to be female or ambiguous. Due to the same insensitivity to testosterone, individuals with complete androgen insensitivity will go through a female puberty as an adolescent, because the testosterone that they are unable to process will convert to estrogen via a process called aromatization (binding with the enzyme aromatase). AIS belongs to a category of testosterone biosynthesis testicular DSDs, and another common condition within this category is 5ARD. Unlike AIS, fetuses with 5 alpha reductase deficiency is not insensitive to testosterone, but rather lacks the enzyme 5 alpha reductase, which causes a fetus with testes to be unable to produce DHT. As mentioned previously, DHT is crucial to the development of external male genitalia, and due to this absence, individuals with 5ARD are born with female or ambiguous genitalia while having a fully functional male reproductive system (testes, prostate, seminal vesicles) otherwise. Cases like this (and a handful of other conditions) commonly cause what we know as “mistaken assignment”, where the assumed sex of the infant does not match what sex their body best functions as, and this mistake may only be caught at puberty.

Another common case is congenital adrenal hyperplasia 21 hydorxylase deficiency, where a deficiency in an enzyme causes the adrenal glands (which helps regulate the body’s endocrine system) to overproduce testosterone in an otherwise XX fetus with ovaries, and this tends to result in female internal organs (uterus, ovaries) with external ambiguous genitalia. Some individuals with CAH experience salt wasting due to the severity of the deficiency’s affect on the adrenal glands, and other side effects/health issues occurring as a result of a DSD is not the rule, but also not uncommon. There are 7 known types of CAH that affects both XX and XY individuals, with vastly different mechanisms and presentations.

Do people with DSDs have a sex?

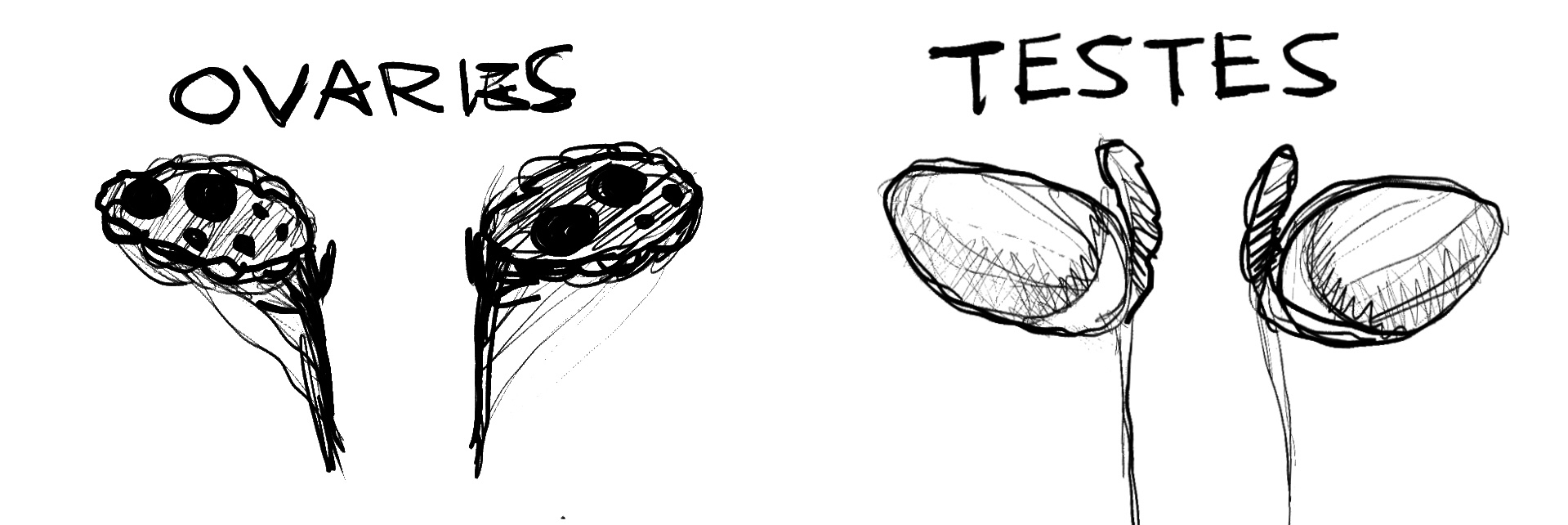

To answer this question, we need to have some better understanding of what kinds of reproductive organs people with DSDs have. Shockingly, most have the exact same or similar gonads to “typical” individuals, just at times with different configurations.

We can understand the different types of gonads that come up in DSDs:

Testes: A number of DSDs result in bilateral testes, or a testis and a streak gonad, making the individual’s gonadal sex to be male. Most typically seen in 46XY DSD, where genitalia or endocrine composition is where difference is seen, testes can also occur in those without a Y chromosome, such as in 46XX SRY+

Ovaries: A number of DSDs will result in bilateral ovaries, with the most common ovarian DSD being CAH (congential adrenal hyperplasia), and differences are seen in genitalia and endocrine composition. In very rare cases, someone with 46XY can have ovaries

Ovotestes: A small portion of DSDs will result in someone having ovotesticular tissue, which is called OTDSD. Someone can also have an ovary and a testis. This is usually caused by either genetic mutation or by chromosomal mosaicism or chimerism

Streak gonads/undifferentiated: If gonads are not differentiated at all, such as in Swyer’s syndrome, the individual usually has a female phenotype (complete mullerian structures). This is the only case where gonads may need to be removed for an individual’s safety, they can easily become cancerous.

And we can also understand the pubertal phenotype, which defines an individual’s secondary sex characteristics (note that each category describes what someone’s body biases, there may still be significant differences):

Female development: estrogen and progesterone dominant, and either develops female secondary sex characteristics (breast and hip growth, menstruation) spontatenously, or with some slight assistance.

Male development: testosterone dominant, and either develops male secondary sex characteristics (bone and muscle growth, voice changes, facial/body hair) spontaenously, or with some slight assistance.

Mixed/Cycling development: in rarer cases, development strays so far from the usual female or male pathway that it could be best described as cycling or simultaneous, and the individual may develop strong characteristics of both

What about genitalia? Don’t we assign sex through genitals?

While it is common practice to assign a gender to an infant via genitalia, and while for people without DSD genitals are an accurate indicator of their sex, this doesn’t always correlate to functional or gonadal sex for intersex people. Mistaken sex assignments happen frequently with some conditions, like 5ARD or OTDSD and CAH. Other times, genitals are ambiguous and it is difficult to determine whether it resembles male or female genitalia, and in and effort to get an infant to “conform” to a category, frequently cosmetic surgeries to alter the appearance of the genitalia is performed. These surgeries often cause a loss of sensation and chronic pain, due to being performed at such a young age. In addition, patients with DSDs are frequently coerced or forced into having their gonads removed due to discovering that they do not match the sex that the individual had initially been registered as, leaving the person with no ability to reproduce or regulate their own hormones.

Images of ambiguous genitalia are rare, and are frequently diagrams that do little to accurately convey what genital ambiguity could look like. In addition, many reference images come up on google from case studies that have taken photos of patients during unethical examination procedures. Ethical awareness about ambiguous genitalia is the first step to acceptance of genitalia that naturally lies outside of the norm. (drawn images of genitals below, avoid if it makes you uncomfortable)

What might someone with a DSD look like?

No two people with a DSD are the same, even if they have the same condition. Our bodies vary from each other the way everyone’s does, and no two interesex people have the same story. The examples below are by no means supposed to generalize what DSDs are like or what the intersex experience is. THey serve simply, as ways to humanize those who experiences these kinds of differences.

5ARD is a DSD that causes the body to be unable ot produce DHT. This will result in a male fetus (XY, testes) to be unable to develop external male genitalia, and instead develop ambgiuous or female appearing genitals. Often, those with 5ARD will be assigned female at birth (meaning, they are raised as girls), and they may find out about their condition when they begin to go through a typical (but unexpected) male puberty. The majority of those with 5ARD raised as girls choose, around puberty, to live as men due to realizing their gonadal/primary sex. This kind of shocking realization is not always easy to handle, and teenagers going through this difficult period of life can always use more psychological and social support.

%202.jpg)

CAIS is a DSD that causes the body to be unable to process/respond to testosterone. A fetus may start off as male, with testes, but due to being unable to respond to testosterone, genitals develop entirely female. Pubertal development is also female, as the body will convert testosterone to estrogen and function off of estrogen if testosterone does not illicit a response. Many girls with CAIS do not find out until late adolescence, when lack of menstruation will spur them to see a doctor. They can feel very alone and different from other women, even though they appear the exact same. Support groups for those with DSDs creates spaces where those who have no chance to speak about their experiences otherwise, can step out of their invisibility.

%202.jpg)

CAH and female OTDSD (ovotesticular DSD with ovarian majority) can result in someone who is reproductively female to be born with ambiguous or male genitalia. Frequently, when they are discovered to be intersex, various surgeries are performed to either create “suitably feminine” genitals, or to emphasise male gender that might have been assigned at birth. This is often done when the individual is too young to consent. Even though conversations around other variations have moved towards caution regarding surgery, the same conversations lag around DSDs where the gonads are female but the outer genialia do not look entirely female. Unfortunately, policies surrounding DSDs are not frequently influenced by cultural biases, and have been historically, heavily influenced by misogyny.

%202.jpg)

Myths and Misconceptions

Are DSDs like being a hermaphrodite?

Contrary to popular belief, as well as older medical misconceptions, people who have DSDs are not hermaphroditic. A true human hermaphrodite, as in someone who can produce both viable eggs and sperm, and is capable of both pregnancy and insemination, has not existed at least according to our current knowledge. Snails are hermaphroditic, for example, but humans are not.

Intersex people have historically been seen as either monsters or gods, and this misconception has caused much stigmatization and fetishization. Modern medicine has not been any kinder, categorizing intersex people into very othering categories and conducting risky cosmetic surgeries on intersex children’s genitalia. In reality, an intersex person often looks no different from a non intersex person when you meet them in your daily life. You have probably met someone intersex in passing or are acquainted with them, but are unaware because you have not seen their unclothed bodies or their medical records. Intersex people are everywhere, living normal lives, with the same hopes and aspirations as anyone else. They can be your classmate, your colleague at the office, your professor or even the doctor you see at the hospital.

.jpg)

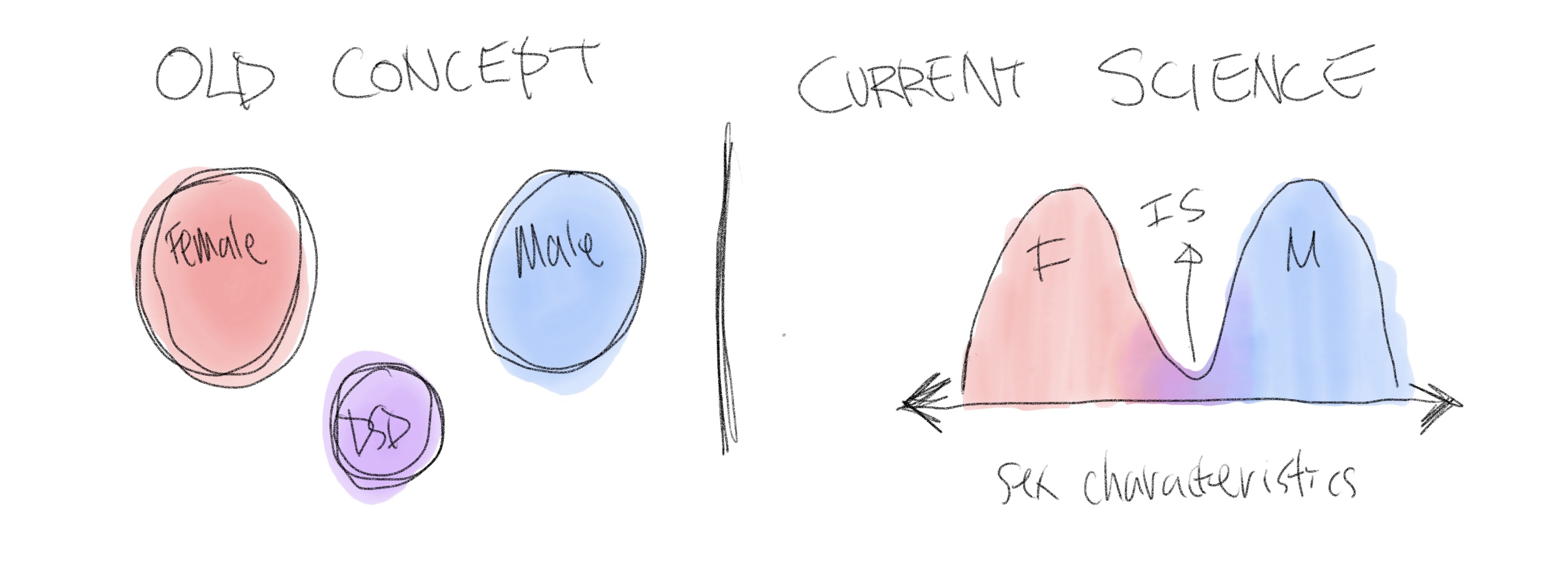

Are DSDs disorders or diseases then?

We used to think that those with DSDs were another category separate from male and female, but we now know that sex characteristics exist on a bimodal spectrum, and for most people with DSDs, they function as either phenotypical/gonadal males or females. This means that the vast majority of people with DSDs either lean male with some atypical or female traits, or lean female with some atypical or male traits. Their differences simply mean that they have traits from somewhere else on the spectrum, and it does not make them diseased or needing to be separated out as a different category. Intersex bodies are simply a natural variation of the existing two sexes.

Are intersex people intellectually disabled?

No, intersex people do not usually have intellectual disabilities. The occurrence rate of intellectual disability for intersex individuals is around the same as for the general population. While certainly a flawed metric, average intelligence quotient (IQ) scores for intersex people are the same as the general population. Less than 5 of the 40+ conditions is associated with intellectual disability, and these specific conditions are fairly uncommon. This is because the genetic differences (even the chromosomal ones) However, intersex people do experience higher rates of neurodivergence, such as autism, ADHD and learning disabilities like dyslexia or dyscalcullia. Some conditions have positive correlation with other disabilities or chronic illnesses, such as Turner’s syndrome individuals having a higher rate of deafnesss or CAH individuals having a higher rate of connective tissue disorders.

Are intersex people/people with DSDs transgender?

There is a popular misconception that those with DSDs are transgender because there is a significant minority who end up living as a different gender in adulthood than childhood. However, the majority of those with DSDs do not have genital/gonadal mismatches, and they stay the gender they were raised. For the minority (around 10-20%) who do change their lived gender, it is usually because they were assigned to a gender that does not correspond to their gonads, and they undergo a puberty in adolescence that doesn’t match their genitalia, and thus change their lived gender. These individuals are also not classed as transgender, because their gender identity is aligned with their body’s sex.

Rather, those with DSDs who have atypical or different gender experiences, can sometimes coin these experiences or their identity as intersex. The vast majority still have a binary gender identity. Those with DSDs frequently refer to their experiences, community and self conceptualization as intersex — an experience outside the typical male or female experience— and will call their medical diagnoses/specific conditions a DSD. Being intersex is much more like the experiences someone with albinism, or an extra limb, may have, as it is a physical difference that affects one’s social and psychological development, and while people like to self describe with the term intersex, “intersex” is not considered a gender identity by most, but rather a descriptor for bodies and experiences.

In conclusion:

People with DSDs do have a sex, just not in.a conventional way. They have a gonadal (primary) sex, and a functional (phenotypical) sex, and the primary and secondary sex may not match like in the case of CAIS. Most intersex people’s bodies function male or female. The idea that those with DSDs do not have a sex, have a “broken” sex, or having an undefinable/fluid sex, has contributed to unethical medical practices of sterilizing and non consensually modifying (usually minors) those with DSDs. People have a right to retain their reproductive organs even if the composition is unconventional, and they have a right to their biological sex and a right to reproduction. There is a lot of stigma surrounding DSDs both in the medical field and in the social sphere, and that stigma largely stems from lack of awareness and education about DSDs, leading to the continuation of unnecessary cosmetic intervention. It is my hope that this website was able ot offer some compassionate but scientific education about the topic of DSDs.

Additional Material

I conducted an interview with an intersex activist on what she felt about the incidence of DSDs and stgima surrounding medical diagnosis and care. She has a lot of great insight, and if you are interested in reading about it, you can find that interview at the end of this page